The classroom door is locked

(the firemen and I keep odd hours)

Desperate men

They offer to break it down with axes

I find the custodian playing cards in the alley

With an unemployed Ph.D. who is trying

To stay close to academics

And we all tumble in

To watch fuzzy blue slides plastered

On a bleak green junior college wall.

The snort and cavort at “Girl Before A Mirror”

They’re used to more literal dismemberments

Of reality

“Is she pregnant or just fat?”

Asks the wise-ass fireman.

“She’s pregnant with meaning,”

I slyly rejoin.

“My kid could draw that good,”

Growls the football-playing fireman

Who wants to go shoot pool.

The economically cynical fireman asks,

“He gets a million bucks for this?”

And the neo-Marxist fireman replies,

“It’s all fixed.

They choose great artists at random

Or through bribery.”

For firemen, reality has only two levels:

The raw and the cooked

And this strange, broken picture seems to them

Only half-baked.

I try to explain the liberation of form,

The influence of modern physics and African art,

The multi-dimensionality of color

But they keep asking, “what is it?”

I finally give in and say

“it’s a woman looking in a mirror.”

The brutally honest social realist fireman says

“I see five boobs and a broken nose.”

We talk (I talk) about ideas of reality

Angles of vision, dreams, levels of reality,

But we keep coming back to feeling:

They don’t have any for this painting.

Firemen are creatures of immediacy:

roof-walkers, heart-starters,

Flame-killers, smoke-breathers,

Answers to the ever-popular question:

“Save me?”

Athletes in action

Staring at a message from Paris, 1932

Which might as well be from another universe.

With authority, the literary critical

Fireman concludes,

“It’s like a cartoon that’s not funny.”

The tabula rasa fireman asks plaintively then,

“Why is he good?”

The question is not simple.

It hangs in the fuzzy blue air

And I wish he had asked the same

About Fran Tarkenton or Mick Jagger.

I gulp and look out the Venetian blinds

Wishing I was hitting two soft yellow tennis balls

With that girl strolling by in the twilight.

Like these students of fire science

She never sees another person in the mirror

Always the same solid pre-medical

Technologist body/mind.

I wonder if I can skip directly to Andrew Wyeth

Or perhaps to a discussion

Of “The Towering Inferno”.

“If Picasso’s good, then the world is crazy,”

Says the radical phenomenologist fireman.

He’s good, all right, and the world

Is not as it seems.

The burnt stairway does not hold;

The doused embers still smolder

Until drenched to the core

Hollowed out, emptied, laid bare

The blind fireman has been listening

Eyes covered with huge white bandages

Where he splashed lye last week.

“I don’t think the woman

Likes what she sees,” he says

A glimmer of fireman feeling

Enough, at this point

Too much analysis can lose the world

And maybe I

Can use some fireman eyes.

Class dismissed. “Watch yourselves

This week,” I add

“Don’t break any mirrors

To save the walls.”

But they are already halfway

To their game of pool, and I’m

On my way home to smoke in bed.

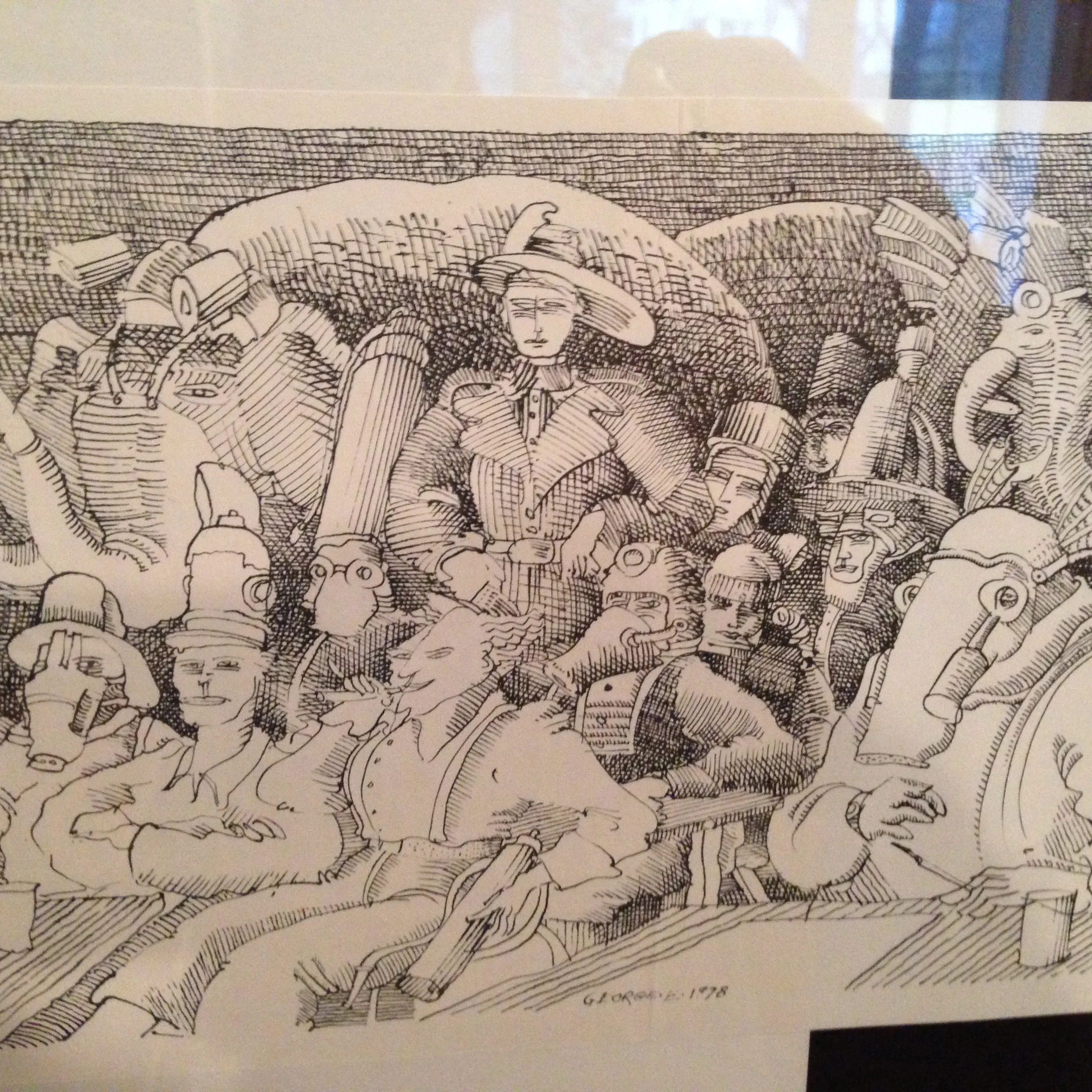

Published in Daemon, 1978 (Illustration by George Evelyn)